By Geoffrey Waterman

Kristin Prevallet was born in Denver, Colorado, and currently resides in Brooklyn, New York. Recipient of a 2007 New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship in poetry, she is the author of numerous books, most recently I, Afterlife: Essay in Mourning Time (Essay Press, 2007). She is a hypnotherapist currently working in Manhattan, and is completing a book of essays entitled Writing Is Never by Itself Alone: Practicing Investigative Poetics.

Kristin Prevallet was born in Denver, Colorado, and currently resides in Brooklyn, New York. Recipient of a 2007 New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship in poetry, she is the author of numerous books, most recently I, Afterlife: Essay in Mourning Time (Essay Press, 2007). She is a hypnotherapist currently working in Manhattan, and is completing a book of essays entitled Writing Is Never by Itself Alone: Practicing Investigative Poetics.

When you read at Temple University, I was impressed by how much the text was expanding through your voice — expanding in the sense of opening up. I’m specifically thinking of the reading of your “shadow poem,” written after Walt Whitman’s “Apostroph.” Is this something you pay particular attention to while writing — a text opening up while being read aloud?

Thanks for hearing this! I’m definitely aware of performing when I read my work out loud. I’m conscious of bringing forward the music of the language, but am very hopeful that every poem I read out loud sounds different because the rhythmic structure of each poem (or prose piece) is different.

The other thing I’m very conscious of is the audience. Some poets seem to not really care about the audience, standing and reading their work as if they are reading to a mirror. And some poets can get away with this with startling effect (sometimes) — but that never worked for me. Probably because I need to connect with people (not rise above them), and so I think of the poetry reading as a performance in which I am putting forth vibrations of energy fluctuations that will be received or rejected at the level of meaning and music. Which means there are many poems I have written but have never read.

“Energy fluctuations” — did I really just say that? Sounds cheesy — but are you catching what I mean?

It seems you want the performance to contain a kind of empathy, whether positive or negative — a sharing by means of the meaning and music. Or do you see yourself more as a transmitter or as a deliverer? This also raises the question of why this might keep poems out of the reading space.

Right — something gets transmitted through music and the play of meaning in language; whether it’s received positively or negatively by the individual bodies in the audience isn’t as important as the intention that I, as a performer, bring to the piece. The intention, in other words, is to deliver — which doesn’t mean a package via UPS (or my favorite, G.O.D.) — but does mean to set something free that will somehow be received. And this varies depending on the work. Some of my work is very confrontational and gets “in the face” of the audience (like this piece on the Web). Other pieces ask the audience to do the work in order to hear it. So there are multiple relationships to the music and meaning of the piece, which shift and fluctuate depending on what the work is trying to do and the energy I am able to put forward to transmit it.

Do you consider the pathway between reader and audience bidirectional? For example, if you perform a piece that is more political, such as “Cruelty and Conquest,” is the audience also transmitting their politics to you? Is there something you receive in performance?

Of course there are bi, poly, multi, uni, etc., fields of exchange between audience and performer happening all the time — but when I’m up there in front of the mic, I’m not thinking about all the noise happening between me and the receivers/audience because that would be quite intense and I’d lose focus on what I am reading/doing. However, there are certainly poets who traverse the fields — Cecilia Vicuna would perhaps be one in the sense that she physically maneuvers between audience and stage using both her body and her voice.

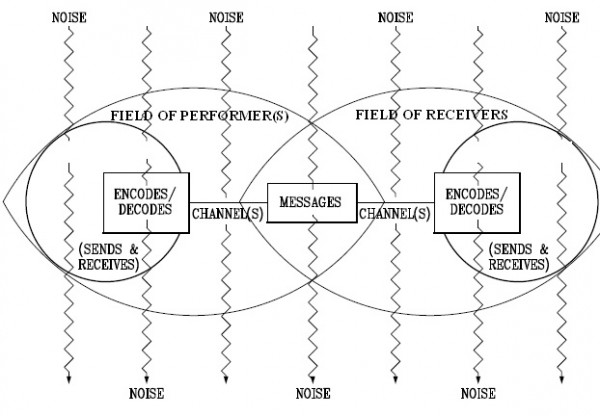

This language is getting a bit abstract — here’s a diagram of what I think this meta-directional energy (transmission, reception, noise) looks like:

Diagram amended from Figure 1, Adler and Elmhorst, “Communication Model,” Communicating at Work, 2002: 9.

Just looking at the diagram can make you lose focus. To get back to specifics, when you read “Apostroph,” I was entranced by the force of your “O!” You had great control over the music and energy, with crescendo and decrescendo. Pardon any vulgarity, but it was orgasmic. Is this something you saw in the Whitman and wanted to emphasize through your writing and reading?

Yeah, isn’t that amazing to think about? This is happening within all conversations — between me and you now, between reader and writer, performer and audience, teacher and student, between lovers, etc.! And it’s happening at the cellular level as well, but that’s another conversation.

“O” orgasmic? That’s quite a compliment. I wrote that poem in 2006 for an anthology called Homage to Whitman. When I first read it, the O’s started doing their O thing, and I just let it go. It wasn’t planned out or rehearsed — in fact, most poems don’t find their music until I’m in front of an audience, reading out loud. Often, I’m surprised about what comes out, and at what point. “Apostroph” was definitely one of the more surprising pieces that I’ve written, and it has legs (glad you noticed!), so that’s why I keep reading it.

Could you talk more about the “shadow poem” as a mode of writing, or as a method of research or excavation (of self and source)?

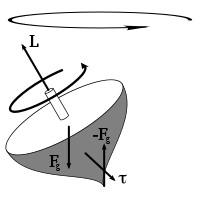

Referring to my “shadowing” of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, after reading one of the sections at Temple, I had a wonderful conversation and brief correspondence with Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and we decided that her notion of “torquing” and my notion of “shadowing” are conversant. (By the way, my notion of shadowing comes from Anne Waldman.) Think about torquing as describing the action of taking a “core” text (for me it was Four Quartets, for Rachel it was George Oppen’s Of Being Numerous) and writing into the energy of every line so that the basic structure of the original is still evident, but the context and meaning of the words change. Check out this diagram:

Diagram by Xavier Snelgrove from Wikimedia Commons.

In the image of the top, there is a center (which is the original poem). Once you start torquing it, the force of the momentum around it causes it to move. So the poem may shift in tone, register, metaphor, and measure, but you can still “sense” the fulcrum of Oppen, or Eliot, or Whitman, etc. But it has been “overlaid,” and so takes on an assuming presence. I wrote to Rachel that “I wonder if ‘shadow’ refers to the end result — not the process or act of sitting down to torque the language, but the shadow that appears to help the reader gain her bearings in the collaboration.…”

To use the physics of the top, there seems to be two ways to control how it spins: angular momentum (L) and torque (tau). So maybe that is the balance between the two — different parts of the same equation?

Perhaps another way to think about the “shadow” is in parallel to shadow theater (not to muddle with your term too much). The method or play becomes the moving of the center farther or closer to the light source, bringing the image in or out of focus and making it appear larger or smaller. It’s more about looking at the effect than the object or process that is casting the shadow. That may be a little too much like the Allegory of the Cave, but does it jibe with what you had in mind?

Well, once we really try and get into it, it’s all about metaphor — it’s hard to talk about it any other way but through the vision field of something else. I do like your shadow theater image, and the idea of the original text as a “light” that goes in and out of focus, sometimes blurring completely as the new text becomes a poem (event in language) in and of itself…I prefer this lingering on the metaphorical realm to getting too far into physics, because this whole idea of shadow/torque is a mental activity — as William Carlos Williams said: “There is no thing that with a twist of the imagination cannot be something else.” Physics leaves little room for that (as it is classically understood).

As for Plato’s allegory, Coldplay’s “Fix You” song, and actually even more so the video, covers everything I both love and hate about Plato and what the imagery of “light” represents culturally. It’s such an omnipresent metaphor.

Light is omnipresent, and often more direct than metaphor. Maybe this is why it’s more important to look at the shadows, because we can more fully engage in the metaphor. Especially today, our culture will whitewash more often than “guide you home and ignite your bones.” Is the subject of light and shadow how you chose some of the work for which you’ve written “shadow poems”?

Wow, you are firing my synapses! So, I used to teach freshman composition, and I always taught the Allegory of the Cave as a means of revealing a metaphor that is so culturally clichéd that it’s everywhere (see the light, free yourself from mental slavery, truth is power, etc.). After reading it out loud with the students and then having them draw it, I played the “Fix You” video and asked them to analyze it in relation to the Allegory of the Cave. It’s just too perfect, whether Chris Martin meant it or not. What always struck me about that assignment is how amazingly successful it was for students, and how dreadfully it failed for me. In other words, it reinforced ideas of “truth” and “knowledge” and “beauty” and led to precious few cultural critiques of how that metaphor oppresses as much as it enlightens.

I followed it with Malcolm X’s education narrative, but still the value of the “light” was vivified for most students. (Obviously, as in any class, there are five or so who take it to another level and question rhetorical supremacy of white = light, etc.)

So, Eliot = white and is equated with Plato’s sun (knowledge, power, status, stature). He’s also got the whole “buried life” thing going on. My “shadowing” of the poem takes the “light” that he so grandiloquently revealed, and recasts it onto a different power source in a different era: Iraq/Afghanistan; cultural depression, and environmental catastrophe. So, yes, I am playing with the light.

I recently participated in a panel at Harvard called “Poetic Fashion and Unfashion: Literary Outliers Roundtable” with Annie Finch, Cate Marvin, and Don Share. We talked about what “embarrasses” us in terms of sources/references that are not cool, or in keeping with current trends in poetics. I spent my time talking about Duncan’s H.D. book and my work on Helen Adam. One of the issues that came up for me was that the contemporary (our poetic “now”) can focus bantering with and resisting sources of power in the poetry world (like Poetry Magazine, perhaps, or The New Yorker), but it’s much more interesting — and I think relevant to the long-term work of poets — to focus on larger systemic and structural issues at play in larger worlds. For me, I find the Ecopoetics project (Skinner, Ijima, Durand, etc.) or the Somatic poetry project (Conrad, Kocik, Stecopoulos, et al.) very relevant to the way I am thinking about writing as well as the way I am enacting participation in the larger world, because these ways of thinking about poetry are generative, as opposed to reactionary.

In other words, I’m cooking up Eliot in a shadow-torque soup not to impress anyone except for those with whom I am in correspondence — where correspondence means a widening sphere of potential influences, friends, and commiserators (not a word, but I like it), both known and unknown. The light comes from the source that you tend. (Which is another way of saying “Which wolf will win? The one you feed”…)

Thanks for being one of them!

I think that’s the best thing to take away from a panel that’s enforcing embarrassment and non-courant (and, by extension, pride and “cool”): be generative and participatory. Thank you, too, for extending your community to me and everyone who will read this interview.

My pleasure.

Read an excerpt from Everywhere Here and in Brooklyn: A Four Quartets.

Photo of Kristin Prevallet: Richard Ryan