By Christopher Schaeffer

Susan Landers, while known primarily as a New York poet, has deep roots in the Philadelphia area, as her ongoing project Franklinstein demonstrates. A combination of memoir, history, and cultural criticism centered around the Germantown neighborhood, she takes her brand of witty, acerbic experimental poetry to the site of her childhood with constantly surprising and exciting results. Landers is also the author of 2003’s 248 mgs., a panic picnic, from O Books, 2007’s Covers, the 2011 Least Weasel chapbook 15: A Poetic Engagement with the Chicago Manual of Style, and What I Was Tweeting While You Were on Facebook, recently released from Perfect Lovers Press.

Susan Landers, while known primarily as a New York poet, has deep roots in the Philadelphia area, as her ongoing project Franklinstein demonstrates. A combination of memoir, history, and cultural criticism centered around the Germantown neighborhood, she takes her brand of witty, acerbic experimental poetry to the site of her childhood with constantly surprising and exciting results. Landers is also the author of 2003’s 248 mgs., a panic picnic, from O Books, 2007’s Covers, the 2011 Least Weasel chapbook 15: A Poetic Engagement with the Chicago Manual of Style, and What I Was Tweeting While You Were on Facebook, recently released from Perfect Lovers Press.

She maintains the Franklinstein Blog and was the editor of the journal Pom2 from 2001-2006, recently digitized and available to read here. She also edited 2013’s Maggie, an online journal about poets and their dogs, which can be read here.

I’d like to ask you about Franklinstein and some questions of genre. On your blog, you talk about the genesis of the project a bit — how the initial idea of a mash-up between Ben Franklin’s Autobiography and Gertrude Stein’s Making of Americans seemed to be “missing a soul,” a soul which turned out to be the local and personal history of Germantown. I’m curious about two things: first, what kind of shape did you see the project as taking before you realized you wanted to bring in this documentary element?

And second, how did you manage this thematic transformation? On the page, it works out wonderfully, but what was the process of getting the sort of conceptual, bricolage-y, abstract side of the project to play nice with the more documentary or even New Narrative-esque angle (I’m thinking in particular of the marvelous shift at the end of “it is with considerable difficulty that I remember the original era of my being”)?

My project started when I could no longer stand the fact that I hadn’t yet read Making of Americans (as a Stein fan) or The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (as a Philadelphian). So, I decided to spend 40 days of my 40th year reading them both and writing down lines that stood out to me — either musically or semantically.

I had no specific use in mind when transcribing the lines; I just thought I’d be able to shape them into something when I was done reading. I ended up with a notebook full of beautiful lines by Stein interrupted by rather banal phrases from Franklin. I thought the chance operations of having somewhat randomly selected text would create something interesting, but, really it was simply derivative.

But then a few months into assembling my notes, I found out about my childhood church closing. While I was no longer a practicing Catholic, I felt saddened by this news. The church had been the site of numerous milestones in my family for generations and was a gorgeous building full of stained glass and art deco murals — including this crazy merman-style Jesus giving stigmata to Francis over the altar.

photo by Ethan Fugate

I decided to see the church one last time before it became one of Philadelphia’s infamous vacant buildings. When I visited the neighborhood, I was struck by the palimpsest quality of Germantown — with its 18th century houses, its great Belgian block road, its 19th century factories, its storefront churches, its rowhomes, its take-outs. Some of its history has been preserved by neglect, some of it preserved with intention, some of it lost, some of it hidden, but all of it intriguing the more and more I researched it.

Quite organically, then, the project became centered around Germantown, and I started using Franklin and Stein to help me tell its story. To do this, I search the electronic versions of the Autobiography and Making of Americans for specific words that fit with whatever story or feeling I am trying to convey, and then weave those lifted lines into the poem.

I’m sort of surprised and delighted by what you said about using electronic versions of the texts to cherry-pick the words the poem needs. I’m thinking about how that might change how I’m looking at it as a “collage text,” which I think people tend to associate with more of a kind of chance operation or drift through the pages. I’m thinking in particular of that great 1990 Joan Rettalack poem, “Not a Cage,” made up out of numerous old books and articles and assembled into this wild, totally dense jungle of words, and then that PoemTalk from Jacket2 a year or so ago in which Jena Osman, Danny Snelson, and Jonathan Monroe were suddenly able to use the tools made available by google books, for example, to pin-point where precisely each little snippet or chunk of language came from, what sources exactly Retallack had used, and so on, and how that operation changed how each of the speakers encountered the original poem.

Maybe I’m just lazy about archives, but do you think the balance of Franklinstein as it exists could have been struck without that ability to make these sort of very specific, very strategic entrances into source texts. I know that just as a PhD student I feel enormously grateful that I can just, say, hit two buttons and search for “plague” or whatever in Paradise Lost rather than trudging downtown and hauling up a concordance every time.

Or if I could ask whether that kind of approach in Franklinstein differed from the approach in 15 Chigago: A Poetic Engagement with the Manual of Style, which, for me at least, does feel like more of a free-play within a particular body of text?

To call this project “collage” is probably a misnomer. While the project had started out as a mash-up, at this stage in my writing, Franklin and Stein operate more as muses. Searching for language in their texts enables me to get fresh perspective and enter the poems from new angles. And because writing is difficult and I can get stymied by the enormity of Germantown’s history or the challenge of writing autobiographically, turning to these texts is a kind of release valve when writing, like letting the steam out of the radiator.

This approach is a little different than the one I took writing 15: A Poetic Engagement with the Chicago Manual of Style. For that, I read the CMS cover to cover and grabbed lines or words I liked, and the poems emerged associatively from my reading. The result is a kind of response to the CMS itself. In my current project, I don’t see myself responding to Franklin or Stein, I see their texts responding to me and Germantown

Everybody I know who is excited about Franklinstein the book is almost as excited about Franklinstein the blog. It’s a great, very surprising space, where I’m never sure if I’m going to find just odd and evocative pieces of local history (like the post about the oldest graffiti in America, a face drawn in blood in the Cliveden Mansion in 1777) or full-blown poems like “ransom for the little ones,” which springs out of a story on America’s first ransomed kidnapping. And then some posts that feel more process-based, like the one juxtaposing your notes towards a poem about church with that great Stephanie Young excerpt.

So do you see the blog as an adjunct to the book, a supplement to it, or just something working happily in the background of the production of the book? How do you approach it, I guess, as part of the fun and work of poetic production? I know, for example, I have a hard time thinking about Anne Boyer’s poetics without thinking of her various interventions via different forms of social media — and Brandon Brown even has a terrific section of a poem that’s predicated on one of her Facebook posts — and I feel sort of similarly about Franklinstein the blog — the way it seems to sort of open out from the text and show this messier array of Germantown and Philadelphia nodes, but in a way that always takes me back to the poems…

Social media has been an essential part of creating this book. Because I live in New York, a lot of my research has been internet-based. What I found out pretty early on is that a lot of Germantown’s history has not been documented (on the internet especially). And much of Germantown’s present — particularly lower southwest Germantown — doesn’t have a huge internet footprint. So, social media became a means for me to meet people who live in Germantown.

Through Flickr I was able to see the neighborhood again, in the amazing work of photographers like Tieshka Smith and Gary Reed. On Twitter, I discovered the Doley sisters of the Rockland St. Project, who are working to transform the neighborhood by revitalizing their block. And on tumblr, I engage with a larger body of artists and historians working in/on Philadelphia, including some ex-Germantowners like James Johnson.

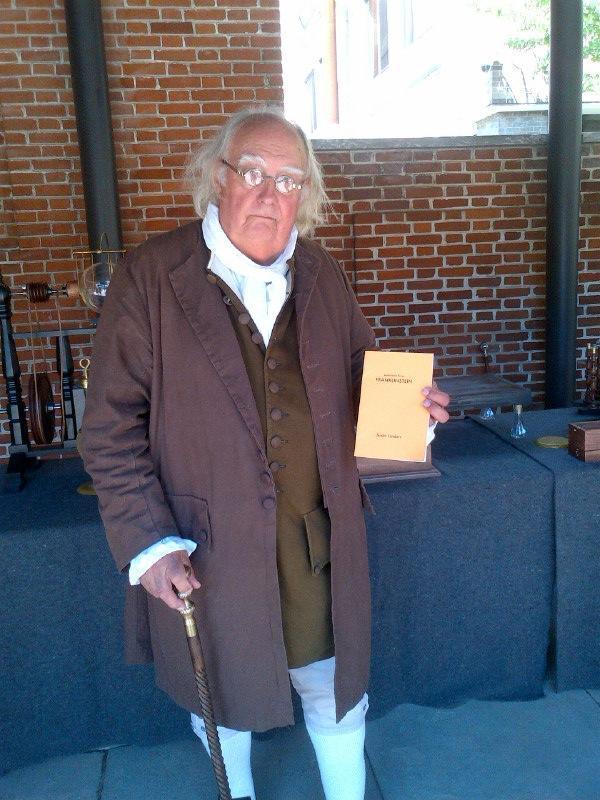

My blog is very much an experimental place, where I want to expose the process of research and writing. To that end, some posts are notes that I will later convert into poems. Others are research findings that may be extraneous to the poems, but that I don’t want to forget. The blog makes me flex different prose writing muscles, and has made me think about how to incorporate photos into my work. It also provides an easy means to keep track of everything project related — sources, publication history, readings, etc.; and since this project is about history, this level of documentation feels especially necessary. It’s also a place for me to post ridiculous pictures of Ben Franklin impersonators.

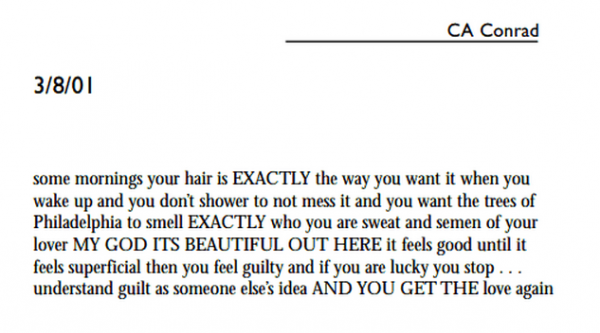

So speaking of your blog, I wanted to ask about Pom2, the magazine you co-edited from 2001-2006, and which has recently been made available digitally. Anybody who looks at the table of contents for any given issue can see that this magazine was completely out of control good. And what blows my mind is that you can see the same communities and conversations that influence so many poets now, 12 years later, finding their feet and making their lines of correspondence right there on the page. Issue 1 alone has Kevins Varrone and Killian, Jenn McCreary, Kristin Prevallet, CA Conrad, Mel Nichols, rubbing textual elbows with Clark Coolidge and Bruce Andrews. And then later, Chris McCreary, Pattie McCarthy, Dodie Bellamy… probably the very earliest Dana Ward poems I’ve ever run into. Every issue is like walking a decade backwards into the weirdest, best party.

The editorial thing at the beginning of the first issue says that “Pom2 seeks to foster and display the many-tongued exchanges taking place among poems […] work that flirts, pinches, shakes hands, gossips or otherwise engages with work printed in previous issues,” and what’s great is that this seems to work out so well. I really do feel like I can see important communities and relationships in contemporary poetry sort of ambling into shape in this journal.

So I suppose I just want to hear whatever you feel like saying about Pom2 — where did it come from, what was it doing, where did it go? — along with a bit of a more specific question about geography. Because what really thrills me about going through these issues is seeing so many major figures in Philadelphia poetry figuring out their projects. Is it just confirmation bias on my part, or was there some connection with the Philly scene that drew all of these poets to Pom2?

Oh! This is so nice to hear! PomPom was a blast to edit. It came from wanting to read a journal full of poems we loved, but which also reflected or created a community. I think we were also influenced by Bernadette Mayer’s experiments and Chain’s annual call for submissions, and wanted to have a kind of prompt for poets to respond to.

The Philly connection came from having met, read, and befriended the Temple poetry contingent when we were in grad school at George Mason. And then there is that AMAZING poem about Philadelphia from CA Conrad.

When I look back on our six issues, I am blown away by our roster, including a few poets who are no longer with us, like Michael Gizzi and kari edwards. I feel so grateful to everyone who chose to participate in our project.

When I look back on our six issues, I am blown away by our roster, including a few poets who are no longer with us, like Michael Gizzi and kari edwards. I feel so grateful to everyone who chose to participate in our project.

Finally, I wanted to ask about a new chapbook you have coming out from Dana Ward’s press, Perfect Lovers Press, called “What I Was Tweeting While You Were on Facebook.” Could you just say a little bit about this project?

In 2009, I was working so much at my non-poetry job, I was finding it very difficult to find the time to write. Twitter offered me a character limitation that was both clock-friendly and inspiring. And I really wasn’t on Facebook (largely because I was horrified by idea of all my worlds colliding publicly). So I just tweeted what I thought might make good lines, and after the first year, I looked back to see if it could be fashioned into a poem. It continued over the course of 3 years, and Dana was gracious enough to publish the chapbook this fall. Like PomPom, it started off as a kind of experiment that evolved over time, but that is also very much of its time. To get a taste of what the book is like, you can listen to me reading from it at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s.

Listen to poems from Franklinstein and What I Was Tweeting While You Were on Facebook